•*†*•

DIS/RE/ARTICULATION & COLONIAL AMNESIA

*.†.*

An Inquiry by J. S.

The title of Eric Gamalinda’s essay ‘English Is Your Mother Tongue / Ang Ingles Ay Tongue ng Ina mo’ serves as a terse–’packed–example of this kind of playfulness. In Filipino, the word tang (which sounds like ‘tongue’) is an abbreviated form of the commonplace insult putang ina mo, which is the functional equivalent of the english phrase ‘fuck you.’ But putang ina mo literally means ‘your mother is a puta’ and of course is Spanish for ‘whore.’ [...] So the second half of Gamalinda’s lingually miscegenous title contains five possible messages: (a) English is your first language; (b) English is your Mother’s language; (c) You are fucked by English; (d) You fuck with English; (e) English is fucked by your mother. While the displacement of vernacular Filipino languages by the languages English and Spanish is a form of colonial violation, if one pays attention to Gamalinda’s syntax that violation in turn is structurally, formally violated by the colonized. The syntax of the second half of Gamalinda’s title is dramatically correct, but sounds stilted in Filipino syntax because Gamalinda choses to use English (‘Ang Ingles Ay and Tongue ng Ina Mo’) instead of Filipino syntax [...] (‘Ang Tongue ng Ina Mo ang Ingles’). [...] In other words, Gamalinda’s translation denaturalizes native syntax but in doing so calls attention to native subterfuge and tactics that undermine the English language.

—Sarita Echavez See, The Decolonized Eye

America’s COLONIAL AMNESIA is the purposeful forgetting and lack of acknowledgement of the American Colonial Empire.1 For the purposes of this paper, I am keeping the scope to how COLONIAL AMNESIA is used as a tool to further perpetuate the harms of colonialism on the Filipino/American. This comes in two forms: first, the destruction and DISARTICULATION of Native Filipino languages; second, the lack of acknowledgement of U.S. Colonial rule of the Philippines in the post/colonial period.

I can recount several instances during my time in the U.S. where my peers had no idea the Philippines was ever a U.S. Colony. Even more unfortunate, some had never heard of the Philippines or could not place it on a world map. It is now apparent to me that this lack of knowledge has led to further violence on the Filipino/American. It is still frustrating to me to see how people in current-day America continue to reference the colonization of the Philippines as simply “U.S. Occupation,” as though their country did not wage war against the Filipino people and force them to be governed, dehumanized, and exploited by the U.S. Colonial Empire. America’s continued COLONIAL AMNESIA is further exemplified by the language used to describe the current 14 U.S. Colonies:

American Samoa

Baker Island

Guam

Howland Island

Jarvis Island

Johnston Atoll

Kingman Reef

Midway Atoll

Navassa Island

The Northern Mariana Islands

Palmyra Atoll

Puerto Rico

The United States Virgin Islands

Wake Atoll

![i]()

![ii]()

![iii]()

![iv]()

![v]()

![vi]()

![vii]()

![viii]()

![ix]()

Flags of American Samoai, Guamii, Howland Atolliii, Johnston Atolliv, Midway Atollv, The Northern Marina Islandsvi, Puerto Ricovii, The United States Virgin Islandsviii, Wake Atollix. Note that some of these flags are “unofficial” but have been or are currently nonetheless used to represent these nations.

The nations, by United States law, are considered “Unincorporated Territories of the United States.”2 The use of such language has been dispersed and normalized in mainstream U.S. media that many people call these nations “U.S. Territories,” rather than actually recognizing that these nations are actually currently colonies of the United States. The U.S. has an AMNESIA of its colonial past and colonial present—the language used to discuss such colonial nations is the U.S.’s purposeful distancing from their Colonial Empire.

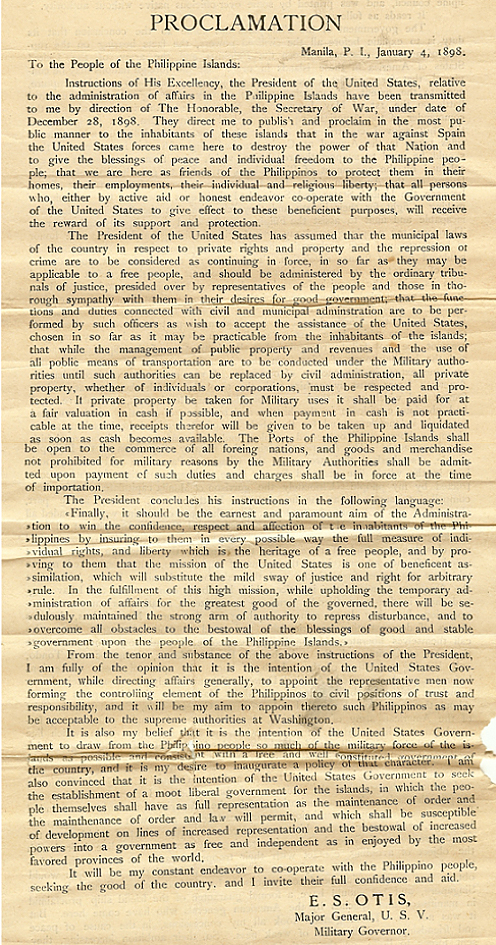

The intentional forgetting of the colonization of Filipinos is exacerbated by the lack of education of the U.S. Colonial Empire (by the U.S. Education system), the perpetuation of racist views of the Majority World, and the framing of the Filipino as “FOREIGN IN A DOMESTIC SENSE.” Even in the official U.S. colonization of the Philippines, the U.S. never actually called the act colonization. Rather, the Philippines was violently forced into the U.S. Colonial Empire through the December 21, 1898 “Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation.”3 The proclamation reads, in part: “it should be the earnest wish and paramount aim of the military administration to win the confidence, respect, and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines by assuring them in every possible way that full measure of individual rights and liberties which is the heritage of free peoples, and by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.”4 From the very beginning of the U.S.’s colonization of the Philippines, the U.S. explicitly framed their expectations of Filipinos: to either benevolently assimilate to the colonial empire, or to face the “mild sway of justice.” Note the use of the phrase “justice,” as though waging war against the independent Philippines was the right thing to do. The Philippine’s refusal to benevolently assimilate resulted Philippine-American War (1899–1902), and the “mild” U.S. State sponsored killing of over 220,000 Filipinos.5✹

![]()

Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation

Along with America’s COLONIAL AMNESIA, I must discuss the loss (or rather REARTICULATION) of many Native Filipino languages. When understanding “the attempted destruction of native languages and the imposition of a singular, dominant language” as the mark of “the catastrophic foundation of a colony,”6 it is impossible to not see the continued effects of colonialism in the Philippines today. Tagalog, the most common Filipino language used (and imposed) in post/colonial Philippines, is a convoluted mix of Native Filipino dialects and Spanish. For example, the common Tagalog greeting “kamusta” comes from the Spanish “como estas,” and “siempre” translates similarly to “of course” in Tagalog but “always” in Spanish. As Tagalog evolved throughout Spanish colonial rule, Spanish words have been transformed in how they are spelled and in some cases pronounced. Take the following list of Tagalog / Spanish / English translations (in that order): kutsilyo / cuchillo / knife, kutsara / cuchara / spoon, tinidor / tenedor / fork, silya / silla / chair, bintana / ventanas / window. As Tagalog spelling tends to be more phonetic, Spanish words have been taken and altered to reflect the actual pronunciation of these words. The evolution of Tagalog spelling is linked to the erasure of pre-colonial ancient Filipino scripts, such as Baybayin. As Latin scripts were not used in the pre-colonial era, the introduction of Latin languages through colonization caused a disconnect in communication and literacy for the colonized Filipino. Spaniards had also enforced which Filipinos would and would not be taught Spanish; this education was reserved for Filipinos of upper-class status. A majority of Filipinos were therefore forced to learn Spanish on their own; the phonetic spellings seen in Tagalog can be understood as the colonized Filipino’s attempt at REARTICULATING their pains so they can be heard and understood by their Spanish colonizers.

The act of loaning words from our colonizer did not stop with the Spanish. Several modern Tagalog words originate from English as well, which has actually led to the adoption of the term “Filipino” (in reference to language and not ethnicity).7 Filipino represents the contemporary evolution of Tagalog due to Western (namely U.S.) influences. Tagalog is understood as the foundational language of Filipino. This more broad term is also used to acknowledge the overlap between many Filipino dialects, and to decenter Tagalog as the dominant language of the Philippines.8✰ Examples of this evolution can be seen in the following Filipino / English translations: adik / drug addict, basketbol / basketball, madyik / magic, lobat / low battery, kyut / cute, ketsap / ketchup, kompyuter / computer, tambay / standby, jeepney / jitney. These loaner words are now so integral to the Filipino language that in our 1973 Philippine Constitution, the Philippines’s official languages were changed from Tagalog to both Pilipino and English, then once again changed to Filipino and English in the 1987 Constitution. Yet the discourse of whether or not Filipinos speak Tagalog, Pilipino, or Filipino continues to this day. The term “Pilipino” was first introduced by the Department of Education in a 1957 memorandum to “remove the regional basis that the term ‘Tagalog’ evoked.”9 This led to the evolution of two distinct (documented) forms of Pilipino; one that was taught in schools with borrowed terms from Spanish and English, and another that fluidly grew in the masses as the Philippine’s lingua franca. With the continued modernization of the Philippines and increased contact with the West, Pilipino continued to grow into the now recognized Filipino language. Tagalog, Pilipino, and Filipino are different forms of the same language, with Filipino now being the most recognized and widely used form.†

Languages are vital for communication, and become even more important when addressing the harms of colonialism. In Spanish and U.S. colonization’s obstruction of Native Filipino languages, I argue that Filipinos have been turned against one another in fighting over which language is most representative of pre/colonial Filipino culture rather than actually ARTICULATING the harms of colonization. In effect, Filipino languages (and overall cultural expression) can be understood through the construct of DISARTICULATION, REARTICULATION, and ARTICULATION (or DIS/RE/ARTICULATION). If to “ARTICULATE” is to “express (an idea or feeling) fluently or coherently,”10 we can understand the DISARTICULATION of Native Filipino languages as the intentional dehumanization and destruction of pre-colonial beliefs, practices, and social structures. In colonization, to DISARTICULATE is to purposefully disrupt and break up the knowledge of the pre-colonial Filipino, for the colonizer refuses to see the colonized subject as human and therefore does not want to even attempt to understand their pre-colonial languages. In this act, colonized Filipinos are forced to either ASSIMILATE and learn the language of their colonizer or to REARTICULATE their Native Languages to a form that is understood by their colonizer. Regardless, in this act of ASSIMILATION or REARTICULATION, the colonized subject is forced to speak in a new language for their pains to be fully heard. Even today, as a post/colonial Filipino, born and raised in the Philippines, I am more able to ARTICULATE the harms and effects of colonization in English rather than in Filipino.

![]()

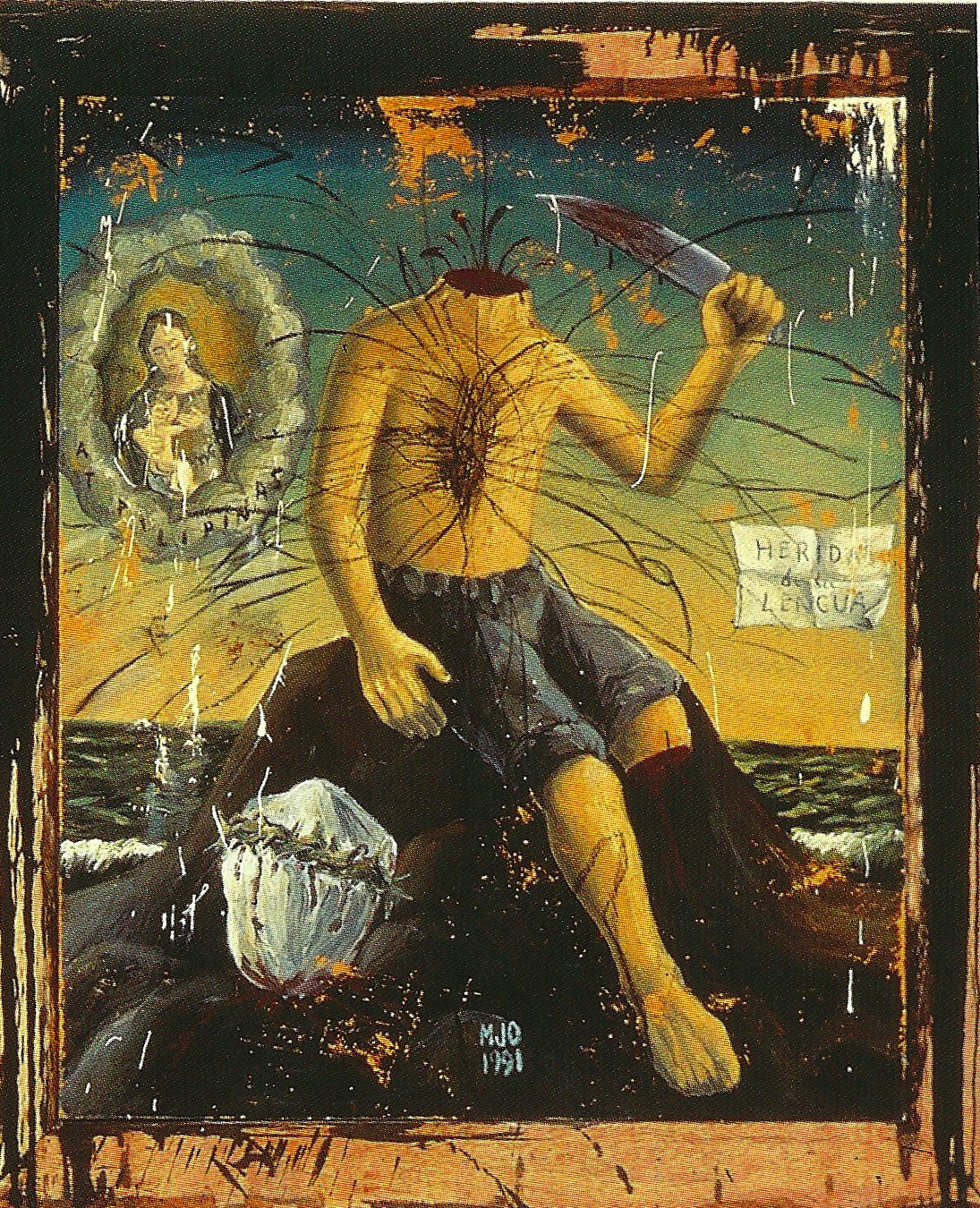

Manuel Ocampo, Heridas de la Lengua, 1991. Oil on canvas. 180 x 155 cm.

The utilization of Spanish for the sake of ARTICULATION can be seen in the work of Filipino American artist Manuel Ocampo. Heridas de la Lengua (Wounds of the Tongue) displays a beheaded subject in the center of the composition. Sarita Echavez See argues that “bereft of language, the colonized subject has nothing left but the body to articulate loss.”11 The beheaded subject sits in front of a portrait of Mother Mary and Jesus, upon a stereotypically beautiful Philippine landscape. This nod to colonialist values however is overshadowed by the blood spewing out of his chest, and his lack of a limb and head. Ocampo’s choice in titling the piece in Spanish symbolizes “the attempted suppression of native languages, [and] underscores the desperate position of the colonized subject who must articulate his or her pain in the language of the colonizer. Because such articulation must occur in Spanish, the attempt at expressing pain reinscribes the power of the colonizer and repeats the violence done to the native lengua.”12 The Spanish word “Lengua” translates both to “tongue” and “language,” therefore referencing the dual “lengua-somatic violence” that the colonized Filipino has faced. In this absurdly gory composition, Ocampo powerfully conveys how the “violence of colonization deprives the colonized subject of both head and tongue, of both subjectivity and language.”13 Ocampo’s clever use of language can also be viewed as a form of RE/ARTICULATION. In his choice of absurdly yet bloodily representing the colonized Filipino, Ocampo is able to address Spanish and American COLONIAL AMNESIA and RE/ARTICULATE the consequences of colonialism.

![]()

Billboards in C5, a major roadway in Metro Manila. Photo by VIVA PH.

![]()

Billboards in a major intersection in Santa Rosa, Laguna. Photo by Jeffrey Hannan.

The frame of DIS/RE/ARTICULATION can also be used to understand Filipino graphic design vernaculars. In a sense, post/colonial Filipino graphic design has been DISARTICULATED by Western Graphic Design principles (A.K.A., the colonizing eye). In viewing the photos of billboards in major Metro Manila intersections above, the Western Graphic Designer in me cringes at the excessive use of photographs, gradients, bright colors, lack of formal compositions/grids, oversaturated photography—the list goes on. Though, the Filipino designer in me understands where this comes from as well as the broader context in which these billboards are found. Like most major roadways in Metro Manila, the billboards in the second image are placed directly above an overpopulated slum in Santa Rosa, where the poorest Filipinos of the area live.‡ The juxtaposition between the placement of absurdly huge & over-ornamented billboards that ultimately aim to sell goods (capitalism!) and the overcrowded slums filled with Filipinos looking to better their lives in the city (also a product of capitalism) is representative of the current state of the Philippines. In a country where the richest continue to get rich at the expense of exploiting the poor, the role of advertising and graphic design is to distract and hide the most undesirable parts of our country. Therefore, maximalism and ornamentation can be understood to have a purpose. In this graphic landscape, the ornamental form, indeed, follows function. I have come to understand that it is almost impossible to evaluate this graphic landscape from a Western perspective. To only focus on the actual Graphic Design of the billboards from a formalist perspective is to take it out of its context and DISARTICULATE how these billboards are actually successful in achieving their intended outcomes (whether these come from a good place or not).

![]()

Fences and advertisements installed in 2012, in preparation for the ADB Annual Meeting. Photo by The Washinigton Post.

The Philippine Government is also guilty of DISARTICULATING the reality of the Filipino in Metro Manila. When the Philippines hosted the Asia Development Bank’s (ADB) 45th annual conference in 2012, the Aquino Government “built a fence on the bridge along the highway that runs from the Ninoy Aquino International Airport to the convention center. Draped over the fence are tarps with signs promoting tourism in the Philippines as well as the ADB meeting.”14 Graphic design is used to obstruct the foreigner’s view of Metro Manila in the hopes of presenting our country as a beautiful vacation spot for tourists (after all, we are the Pearl of the Orient!). This “scandal” gained media traction and backlash which only led to government officials defending this move. Francis Tolentino, chairman of the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority “told the AP that the government needs to show that Metro Manila is orderly. ‘I see nothing wrong with beautifying our surroundings.’”15 Tolentino’s linking of these graphic advertisements to “beautifying” our city demonstrates the inherent use of graphic design in the Philippines as a form of beautification or ornamentation. This may explain our desire to see and create designs that are over-the-top and ornamented in every possible space, as though we need a distraction from our (equally chaotic) lived reality. Thus, we can understand Filipino graphic design both as a tool for DISARTICULATION as well as a field that has been DISARTICULATED by Western Graphic Design standards.

![]()

Hiding slums from prominent foreign visitors has been repeated many times over by the Philippine government. The photo above is from the 2015 visit of the Pope.✦ This time, however, the government omitted any type of ornamentation on the fences. In this case, the government relied on minimalism and the whiteness of the fence to hide slums from the Pope, the most prominent Catholic figure. Beautification via minimalism! A rarity for the Filipino. Photo by Shaun Higson.

The troublesome, and rather polarizing, act of RE/ARTICULATING our nationalistic pride through graphic design exhibited itself when the Philiippines hosted the 2019 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games. The hosting of the event was seen by many Filipinos as an opportunity to present our country as polished as possible to all participating nations. The Duterte Administration similarly saw this as the opportunity to frame the Philippines as a country of importance in Southeast Asia; so much so that the Philippine Government poured over ₱6 Billion Philippine Pesos (~US$118 million) in funding for the games. The handling of the SEA Games by the Philippine Government as a whole, however, had the opposite effect. Many Filipinos exclaimed their outright embarrassment in how the SEA Games presented the Philippines.16 The biggest criticisms came from the use of funds, as well as the location of the new sports complex that was built as the hub for the event. The New Clark City Sports Complex did not only “displace the Aetas Indigenous communities” that have historically lived on these lands, but has also come “to represent extravagance and overspending in a country where about 17 percent of the more than 100 million population does not earn enough to cover their basic needs.”17 In the further consideration of the large budget, Filipinos had a strong reaction to the actual branding and design-related elements for the Games.

![]()

Official 2019 SEA Games Logo.

The official logo clearly takes from the Olympics logo—another example of how Filipinos look to and borrow from the West when the designer cannot fully ARTICULATE Filipino pride with their own voice. The logo is made up of 11 circles (symbolizing the 11 participating nations) and is arranged to form the Philippine islands. The logo, formally, isn’t that terrible, but is evidently a misguided attempt at referencing the minimalist Olympics logo. The Filipino’s (maximal) attempt at minimalist logo design was not well received by Filipinos; it ended up trending on Twitter and Facebook, with many remarks like the following:

The sentiment among all these comments is simply that Filipinos wanted More. Minimalism did not cut it; especially when representing our nation. The use of minimalism in this context can be understood as the failure for the designs to RE/ARTICULATE our culture and country to an acceptable standard. Many local Filipinos (designers or not!) were compelled to create their own logos—to ARTICULATE the Philippines in a More maximal sense. These logo redesigns got so much traction that many local newspapers like the Philippine Star and Rappler even covered the redesigns. For once, graphic design to represent our country (rather than for the sale of goods) was being discussed on mainstream Filipino media. Although I must point out that the fixation on improving this logo was more about how the Philippines would be perceived by other foreign nations, and less about how graphic design can be used as a form of agency in the Filipino setting. The online discourse evolved to Twitter users claiming that these redesigns were all better, mostly because of the increased intricacy. Clearly, Filipinos have an expectation of what good design is (it must look like it took time!). This is further exacerbated once tying it to the ₱6 Billion budget. These designs cannot come off as cheap! And in the Philippines, cheapness equates to minimalism, while wealth is manifested through maximalism.

These logo redesigns are simultaneously better and worse than the official logo. There are maximal elements that I see as speaking more to Filipino identity than the official logo, but the clear lack of formal Graphic Design principles in some of these designs make them fall flat… Regardless, the inclusion of More graphic elements to these redesigns was accepted and celebrated by Filiipinos.

![07]()

![08]()

![09]()

![10]()

![11]()

![12]()

![13]()

![14]()

![15]() Redesigns by 07} @kvpng,20 08} @luisdomingo,21 09} @raphaelmigue,22 10} @bobfreking,23 11} @mhernandezmark,23 12} @elsplane,23 13} @klpotente,24 14} @kendidreamer,25 15} @roilanmarlang26

Redesigns by 07} @kvpng,20 08} @luisdomingo,21 09} @raphaelmigue,22 10} @bobfreking,23 11} @mhernandezmark,23 12} @elsplane,23 13} @klpotente,24 14} @kendidreamer,25 15} @roilanmarlang26

In doing this research, I am ultimately attempting to RE/ARTICULATE post/de/colonial Filipino graphic design in order to legitimize my work in a Western design and educational setting. In other words, like Ocampo, I am forced to speak in the language of my colonizer for my work would otherwise be seen as “Bad Graphic Design.” In this process, I am “repeating the violence”27 of America’s COLONIAL AMNESIA while simultaneously addressing it. I therefore also see this work as vital for a Filipino audience. Although the graphic design industry and community continues to grow in the Philippines, there still has yet to be a formalized educational program that teaches and studies Filipino Graphic Design beyond its commercial and capitalistic capabilities.✢ I understand our current state of Filipino graphic design as our attempt to REARTICULATE our overall field and practice (for both Filipino and Western audiences), as we continue to produce GOOD BAD DESIGN through the tool of CREATIVE MISPRONUNCIATION.

I can recount several instances during my time in the U.S. where my peers had no idea the Philippines was ever a U.S. Colony. Even more unfortunate, some had never heard of the Philippines or could not place it on a world map. It is now apparent to me that this lack of knowledge has led to further violence on the Filipino/American. It is still frustrating to me to see how people in current-day America continue to reference the colonization of the Philippines as simply “U.S. Occupation,” as though their country did not wage war against the Filipino people and force them to be governed, dehumanized, and exploited by the U.S. Colonial Empire. America’s continued COLONIAL AMNESIA is further exemplified by the language used to describe the current 14 U.S. Colonies:

American Samoa

Baker Island

Guam

Howland Island

Jarvis Island

Johnston Atoll

Kingman Reef

Midway Atoll

Navassa Island

The Northern Mariana Islands

Palmyra Atoll

Puerto Rico

The United States Virgin Islands

Wake Atoll

Flags of American Samoai, Guamii, Howland Atolliii, Johnston Atolliv, Midway Atollv, The Northern Marina Islandsvi, Puerto Ricovii, The United States Virgin Islandsviii, Wake Atollix. Note that some of these flags are “unofficial” but have been or are currently nonetheless used to represent these nations.

The nations, by United States law, are considered “Unincorporated Territories of the United States.”2 The use of such language has been dispersed and normalized in mainstream U.S. media that many people call these nations “U.S. Territories,” rather than actually recognizing that these nations are actually currently colonies of the United States. The U.S. has an AMNESIA of its colonial past and colonial present—the language used to discuss such colonial nations is the U.S.’s purposeful distancing from their Colonial Empire.

The intentional forgetting of the colonization of Filipinos is exacerbated by the lack of education of the U.S. Colonial Empire (by the U.S. Education system), the perpetuation of racist views of the Majority World, and the framing of the Filipino as “FOREIGN IN A DOMESTIC SENSE.” Even in the official U.S. colonization of the Philippines, the U.S. never actually called the act colonization. Rather, the Philippines was violently forced into the U.S. Colonial Empire through the December 21, 1898 “Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation.”3 The proclamation reads, in part: “it should be the earnest wish and paramount aim of the military administration to win the confidence, respect, and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines by assuring them in every possible way that full measure of individual rights and liberties which is the heritage of free peoples, and by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.”4 From the very beginning of the U.S.’s colonization of the Philippines, the U.S. explicitly framed their expectations of Filipinos: to either benevolently assimilate to the colonial empire, or to face the “mild sway of justice.” Note the use of the phrase “justice,” as though waging war against the independent Philippines was the right thing to do. The Philippine’s refusal to benevolently assimilate resulted Philippine-American War (1899–1902), and the “mild” U.S. State sponsored killing of over 220,000 Filipinos.5✹

Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation

Along with America’s COLONIAL AMNESIA, I must discuss the loss (or rather REARTICULATION) of many Native Filipino languages. When understanding “the attempted destruction of native languages and the imposition of a singular, dominant language” as the mark of “the catastrophic foundation of a colony,”6 it is impossible to not see the continued effects of colonialism in the Philippines today. Tagalog, the most common Filipino language used (and imposed) in post/colonial Philippines, is a convoluted mix of Native Filipino dialects and Spanish. For example, the common Tagalog greeting “kamusta” comes from the Spanish “como estas,” and “siempre” translates similarly to “of course” in Tagalog but “always” in Spanish. As Tagalog evolved throughout Spanish colonial rule, Spanish words have been transformed in how they are spelled and in some cases pronounced. Take the following list of Tagalog / Spanish / English translations (in that order): kutsilyo / cuchillo / knife, kutsara / cuchara / spoon, tinidor / tenedor / fork, silya / silla / chair, bintana / ventanas / window. As Tagalog spelling tends to be more phonetic, Spanish words have been taken and altered to reflect the actual pronunciation of these words. The evolution of Tagalog spelling is linked to the erasure of pre-colonial ancient Filipino scripts, such as Baybayin. As Latin scripts were not used in the pre-colonial era, the introduction of Latin languages through colonization caused a disconnect in communication and literacy for the colonized Filipino. Spaniards had also enforced which Filipinos would and would not be taught Spanish; this education was reserved for Filipinos of upper-class status. A majority of Filipinos were therefore forced to learn Spanish on their own; the phonetic spellings seen in Tagalog can be understood as the colonized Filipino’s attempt at REARTICULATING their pains so they can be heard and understood by their Spanish colonizers.

The act of loaning words from our colonizer did not stop with the Spanish. Several modern Tagalog words originate from English as well, which has actually led to the adoption of the term “Filipino” (in reference to language and not ethnicity).7 Filipino represents the contemporary evolution of Tagalog due to Western (namely U.S.) influences. Tagalog is understood as the foundational language of Filipino. This more broad term is also used to acknowledge the overlap between many Filipino dialects, and to decenter Tagalog as the dominant language of the Philippines.8✰ Examples of this evolution can be seen in the following Filipino / English translations: adik / drug addict, basketbol / basketball, madyik / magic, lobat / low battery, kyut / cute, ketsap / ketchup, kompyuter / computer, tambay / standby, jeepney / jitney. These loaner words are now so integral to the Filipino language that in our 1973 Philippine Constitution, the Philippines’s official languages were changed from Tagalog to both Pilipino and English, then once again changed to Filipino and English in the 1987 Constitution. Yet the discourse of whether or not Filipinos speak Tagalog, Pilipino, or Filipino continues to this day. The term “Pilipino” was first introduced by the Department of Education in a 1957 memorandum to “remove the regional basis that the term ‘Tagalog’ evoked.”9 This led to the evolution of two distinct (documented) forms of Pilipino; one that was taught in schools with borrowed terms from Spanish and English, and another that fluidly grew in the masses as the Philippine’s lingua franca. With the continued modernization of the Philippines and increased contact with the West, Pilipino continued to grow into the now recognized Filipino language. Tagalog, Pilipino, and Filipino are different forms of the same language, with Filipino now being the most recognized and widely used form.†

Languages are vital for communication, and become even more important when addressing the harms of colonialism. In Spanish and U.S. colonization’s obstruction of Native Filipino languages, I argue that Filipinos have been turned against one another in fighting over which language is most representative of pre/colonial Filipino culture rather than actually ARTICULATING the harms of colonization. In effect, Filipino languages (and overall cultural expression) can be understood through the construct of DISARTICULATION, REARTICULATION, and ARTICULATION (or DIS/RE/ARTICULATION). If to “ARTICULATE” is to “express (an idea or feeling) fluently or coherently,”10 we can understand the DISARTICULATION of Native Filipino languages as the intentional dehumanization and destruction of pre-colonial beliefs, practices, and social structures. In colonization, to DISARTICULATE is to purposefully disrupt and break up the knowledge of the pre-colonial Filipino, for the colonizer refuses to see the colonized subject as human and therefore does not want to even attempt to understand their pre-colonial languages. In this act, colonized Filipinos are forced to either ASSIMILATE and learn the language of their colonizer or to REARTICULATE their Native Languages to a form that is understood by their colonizer. Regardless, in this act of ASSIMILATION or REARTICULATION, the colonized subject is forced to speak in a new language for their pains to be fully heard. Even today, as a post/colonial Filipino, born and raised in the Philippines, I am more able to ARTICULATE the harms and effects of colonization in English rather than in Filipino.

Manuel Ocampo, Heridas de la Lengua, 1991. Oil on canvas. 180 x 155 cm.

The utilization of Spanish for the sake of ARTICULATION can be seen in the work of Filipino American artist Manuel Ocampo. Heridas de la Lengua (Wounds of the Tongue) displays a beheaded subject in the center of the composition. Sarita Echavez See argues that “bereft of language, the colonized subject has nothing left but the body to articulate loss.”11 The beheaded subject sits in front of a portrait of Mother Mary and Jesus, upon a stereotypically beautiful Philippine landscape. This nod to colonialist values however is overshadowed by the blood spewing out of his chest, and his lack of a limb and head. Ocampo’s choice in titling the piece in Spanish symbolizes “the attempted suppression of native languages, [and] underscores the desperate position of the colonized subject who must articulate his or her pain in the language of the colonizer. Because such articulation must occur in Spanish, the attempt at expressing pain reinscribes the power of the colonizer and repeats the violence done to the native lengua.”12 The Spanish word “Lengua” translates both to “tongue” and “language,” therefore referencing the dual “lengua-somatic violence” that the colonized Filipino has faced. In this absurdly gory composition, Ocampo powerfully conveys how the “violence of colonization deprives the colonized subject of both head and tongue, of both subjectivity and language.”13 Ocampo’s clever use of language can also be viewed as a form of RE/ARTICULATION. In his choice of absurdly yet bloodily representing the colonized Filipino, Ocampo is able to address Spanish and American COLONIAL AMNESIA and RE/ARTICULATE the consequences of colonialism.

Billboards in C5, a major roadway in Metro Manila. Photo by VIVA PH.

Billboards in a major intersection in Santa Rosa, Laguna. Photo by Jeffrey Hannan.

The frame of DIS/RE/ARTICULATION can also be used to understand Filipino graphic design vernaculars. In a sense, post/colonial Filipino graphic design has been DISARTICULATED by Western Graphic Design principles (A.K.A., the colonizing eye). In viewing the photos of billboards in major Metro Manila intersections above, the Western Graphic Designer in me cringes at the excessive use of photographs, gradients, bright colors, lack of formal compositions/grids, oversaturated photography—the list goes on. Though, the Filipino designer in me understands where this comes from as well as the broader context in which these billboards are found. Like most major roadways in Metro Manila, the billboards in the second image are placed directly above an overpopulated slum in Santa Rosa, where the poorest Filipinos of the area live.‡ The juxtaposition between the placement of absurdly huge & over-ornamented billboards that ultimately aim to sell goods (capitalism!) and the overcrowded slums filled with Filipinos looking to better their lives in the city (also a product of capitalism) is representative of the current state of the Philippines. In a country where the richest continue to get rich at the expense of exploiting the poor, the role of advertising and graphic design is to distract and hide the most undesirable parts of our country. Therefore, maximalism and ornamentation can be understood to have a purpose. In this graphic landscape, the ornamental form, indeed, follows function. I have come to understand that it is almost impossible to evaluate this graphic landscape from a Western perspective. To only focus on the actual Graphic Design of the billboards from a formalist perspective is to take it out of its context and DISARTICULATE how these billboards are actually successful in achieving their intended outcomes (whether these come from a good place or not).

Fences and advertisements installed in 2012, in preparation for the ADB Annual Meeting. Photo by The Washinigton Post.

The Philippine Government is also guilty of DISARTICULATING the reality of the Filipino in Metro Manila. When the Philippines hosted the Asia Development Bank’s (ADB) 45th annual conference in 2012, the Aquino Government “built a fence on the bridge along the highway that runs from the Ninoy Aquino International Airport to the convention center. Draped over the fence are tarps with signs promoting tourism in the Philippines as well as the ADB meeting.”14 Graphic design is used to obstruct the foreigner’s view of Metro Manila in the hopes of presenting our country as a beautiful vacation spot for tourists (after all, we are the Pearl of the Orient!). This “scandal” gained media traction and backlash which only led to government officials defending this move. Francis Tolentino, chairman of the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority “told the AP that the government needs to show that Metro Manila is orderly. ‘I see nothing wrong with beautifying our surroundings.’”15 Tolentino’s linking of these graphic advertisements to “beautifying” our city demonstrates the inherent use of graphic design in the Philippines as a form of beautification or ornamentation. This may explain our desire to see and create designs that are over-the-top and ornamented in every possible space, as though we need a distraction from our (equally chaotic) lived reality. Thus, we can understand Filipino graphic design both as a tool for DISARTICULATION as well as a field that has been DISARTICULATED by Western Graphic Design standards.

Hiding slums from prominent foreign visitors has been repeated many times over by the Philippine government. The photo above is from the 2015 visit of the Pope.✦ This time, however, the government omitted any type of ornamentation on the fences. In this case, the government relied on minimalism and the whiteness of the fence to hide slums from the Pope, the most prominent Catholic figure. Beautification via minimalism! A rarity for the Filipino. Photo by Shaun Higson.

The troublesome, and rather polarizing, act of RE/ARTICULATING our nationalistic pride through graphic design exhibited itself when the Philiippines hosted the 2019 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games. The hosting of the event was seen by many Filipinos as an opportunity to present our country as polished as possible to all participating nations. The Duterte Administration similarly saw this as the opportunity to frame the Philippines as a country of importance in Southeast Asia; so much so that the Philippine Government poured over ₱6 Billion Philippine Pesos (~US$118 million) in funding for the games. The handling of the SEA Games by the Philippine Government as a whole, however, had the opposite effect. Many Filipinos exclaimed their outright embarrassment in how the SEA Games presented the Philippines.16 The biggest criticisms came from the use of funds, as well as the location of the new sports complex that was built as the hub for the event. The New Clark City Sports Complex did not only “displace the Aetas Indigenous communities” that have historically lived on these lands, but has also come “to represent extravagance and overspending in a country where about 17 percent of the more than 100 million population does not earn enough to cover their basic needs.”17 In the further consideration of the large budget, Filipinos had a strong reaction to the actual branding and design-related elements for the Games.

Official 2019 SEA Games Logo.

The official logo clearly takes from the Olympics logo—another example of how Filipinos look to and borrow from the West when the designer cannot fully ARTICULATE Filipino pride with their own voice. The logo is made up of 11 circles (symbolizing the 11 participating nations) and is arranged to form the Philippine islands. The logo, formally, isn’t that terrible, but is evidently a misguided attempt at referencing the minimalist Olympics logo. The Filipino’s (maximal) attempt at minimalist logo design was not well received by Filipinos; it ended up trending on Twitter and Facebook, with many remarks like the following:

“The official one looks like we didn't even try to put effort. Shame” —@raphaelmiguel18

“When u had 3 months to finish your job but u decide to do it in 1 last day of your deadline” —Lê Vũ Minh Hoàng19

“Reveal something different NOW.” —Jericho Bullecer19

“This is the ugliest Logo Ive ever seen in my entire life. Please do some changes.” —Oyaji San19

“The creation of the SEA Games 2019 Official Logo was?... VERY INCOMPETENT!” —Roycemonde Khristoff Christopher Ramos15

“this is the logo that made you say ‘I HATE TO BECOME A FILIPINO’. What a GARBAGE LOGO that will be remembered in Philippine history.” —James Oreily19

“I thought this was a sample logo? How come it’s still this way. It is so underwhelming.” —Sarah Tamissa Alcantara19

These logo redesigns are simultaneously better and worse than the official logo. There are maximal elements that I see as speaking more to Filipino identity than the official logo, but the clear lack of formal Graphic Design principles in some of these designs make them fall flat… Regardless, the inclusion of More graphic elements to these redesigns was accepted and celebrated by Filiipinos.

In doing this research, I am ultimately attempting to RE/ARTICULATE post/de/colonial Filipino graphic design in order to legitimize my work in a Western design and educational setting. In other words, like Ocampo, I am forced to speak in the language of my colonizer for my work would otherwise be seen as “Bad Graphic Design.” In this process, I am “repeating the violence”27 of America’s COLONIAL AMNESIA while simultaneously addressing it. I therefore also see this work as vital for a Filipino audience. Although the graphic design industry and community continues to grow in the Philippines, there still has yet to be a formalized educational program that teaches and studies Filipino Graphic Design beyond its commercial and capitalistic capabilities.✢ I understand our current state of Filipino graphic design as our attempt to REARTICULATE our overall field and practice (for both Filipino and Western audiences), as we continue to produce GOOD BAD DESIGN through the tool of CREATIVE MISPRONUNCIATION.

1 Sarita Echavez See, The Decolonized Eye: Filipino American Art and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

2 “Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations,” U.S. Department of the Interior, Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/politicatypes

3 “The Philippine Revolution,” Library of Congress, accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/collections/spanish-american-war-in-motion-pictures/articles-and-essays/the-motion-picture-camera-goes-to-war/the-philippine-revolution/?fa=original-format%3Afilm%2C+video#:~:text=On%20December%2021%2C%201898%2C%20President,colonizing%20policies%20in%20the%20Philippines.&text=By%20February%204%2C%20the%20Philippine,were%20killed%20by%20U.S.%20troops.

4 Hazel M. McFerson, Mixed Blessing: The Impact of the American Colonial Experience on Politics and Society in the Philippines (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group), 2013.

5 “The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902,” United States Office of the Historian, accessed March 17, 2021. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/war#:~:text=The%20ensuing%20Philippine%2DAmerican%20War,violence%2C%20famine%2C%20and%20disease.

6 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

7 Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, “Filipino and Tagalog, Not So Simple,” Santiago Villafania: Philippine Pen, August 24, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20140522052247/http://svillafania.philippinepen.ph/2007/08/articles-filipino-and-tagalog-not-so.html

8 Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, “Filipino, Pilipino and Tagalog,” Philippine Inquirer, November 14, 2018, https://www.scribd.com/document/282384536/Filipino-Pilipino-and-Tagalog-By-Ricardo-Ma-Duran-Nolasco

9 Ibid.

10 New Oxford American Dictionary, “Articulate,” accessed via Apple Dictionary on February 12, 2021.

11 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

12 See, The Decolonized Eye, 8.

13 Ibid.

14 Jessica Evans, “Philippines: Officials Hide Poor From Development Meeting,” Human Rights Watch, April 30, 2012. https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/03/philippines-officials-hide-poor-development-meeting

15 Ibid.

16 Rappler Staff, “#SEAGamesFail: Netizens embarrassed by Philippines' SEA Games hosting,” Rappler, November 25, 2019. https://www.rappler.com/sports/netizens-embarrassed-philippines-hosting-2019 17 Ana P. Santos, “SEA Games: Medals and controversy for the Philippines,” Al Jazeera, December 11, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/sports/2019/12/11/sea-games-medals-and-controversy-for-the-philippines

18 @raphaelmiguel, “Philippine 2019 Sea Games logo mockup,” Twitter, August 20, 2018. https://twitter.com/raphaelmiguel/status/1031604447795793920

19 2019 SEA Games, Profile Photo, Comments Section, Facebook, November 28, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/2019seagamesph/photos/a.1982277961864301/1989464314478999

20 @kvpngk, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

21 @luisddomingo, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

22 @raphaeelmiguel, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

23Designs by Twitter users @ bobfreking, @mhernandezmark and @elsplanet. Collagee taken from "Graphic designers reimagine 2019 SEA Games logo," by Patricia Lourdes Viray for Philstar, August 21, 2018.

24 @klpotente, Twitter, August 21, 2018.

25 @kendidreamer, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

26 @roilanmarlang, Twitter, August 21, 2018.

27 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

2 “Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations,” U.S. Department of the Interior, Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/politicatypes

3 “The Philippine Revolution,” Library of Congress, accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/collections/spanish-american-war-in-motion-pictures/articles-and-essays/the-motion-picture-camera-goes-to-war/the-philippine-revolution/?fa=original-format%3Afilm%2C+video#:~:text=On%20December%2021%2C%201898%2C%20President,colonizing%20policies%20in%20the%20Philippines.&text=By%20February%204%2C%20the%20Philippine,were%20killed%20by%20U.S.%20troops.

4 Hazel M. McFerson, Mixed Blessing: The Impact of the American Colonial Experience on Politics and Society in the Philippines (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group), 2013.

5 “The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902,” United States Office of the Historian, accessed March 17, 2021. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/war#:~:text=The%20ensuing%20Philippine%2DAmerican%20War,violence%2C%20famine%2C%20and%20disease.

6 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

7 Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, “Filipino and Tagalog, Not So Simple,” Santiago Villafania: Philippine Pen, August 24, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20140522052247/http://svillafania.philippinepen.ph/2007/08/articles-filipino-and-tagalog-not-so.html

8 Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, “Filipino, Pilipino and Tagalog,” Philippine Inquirer, November 14, 2018, https://www.scribd.com/document/282384536/Filipino-Pilipino-and-Tagalog-By-Ricardo-Ma-Duran-Nolasco

9 Ibid.

10 New Oxford American Dictionary, “Articulate,” accessed via Apple Dictionary on February 12, 2021.

11 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

12 See, The Decolonized Eye, 8.

13 Ibid.

14 Jessica Evans, “Philippines: Officials Hide Poor From Development Meeting,” Human Rights Watch, April 30, 2012. https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/03/philippines-officials-hide-poor-development-meeting

15 Ibid.

16 Rappler Staff, “#SEAGamesFail: Netizens embarrassed by Philippines' SEA Games hosting,” Rappler, November 25, 2019. https://www.rappler.com/sports/netizens-embarrassed-philippines-hosting-2019 17 Ana P. Santos, “SEA Games: Medals and controversy for the Philippines,” Al Jazeera, December 11, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/sports/2019/12/11/sea-games-medals-and-controversy-for-the-philippines

18 @raphaelmiguel, “Philippine 2019 Sea Games logo mockup,” Twitter, August 20, 2018. https://twitter.com/raphaelmiguel/status/1031604447795793920

19 2019 SEA Games, Profile Photo, Comments Section, Facebook, November 28, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/2019seagamesph/photos/a.1982277961864301/1989464314478999

20 @kvpngk, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

21 @luisddomingo, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

22 @raphaeelmiguel, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

23Designs by Twitter users @ bobfreking, @mhernandezmark and @elsplanet. Collagee taken from "Graphic designers reimagine 2019 SEA Games logo," by Patricia Lourdes Viray for Philstar, August 21, 2018.

24 @klpotente, Twitter, August 21, 2018.

25 @kendidreamer, Twitter, August 20, 2018.

26 @roilanmarlang, Twitter, August 21, 2018.

27 See, The Decolonized Eye, 6.

✹ The actual number of lives lost is still unclear today. Other estimates by the Unversity of the Philippinies and Filipino Historians place the estimate of Filipino soldier and civilian lives lost to upwards of 500,000 to 1,000,000.

✰ Tagalog was actually chosen as one of the national languages for the Philippines out of convenience. Once independence was gained, Tagalog was the predominant Filipino language spoken in Metro Manila. The classification of Tagalog as the “main” Filipino language has arguably led to the inadvertent erasure of other Filipino languages and dialects. These languages differ enough that if I heard someone speaking Cebuano or Ilocano, I would recognize it as a Filipino language but not be able to understand a majority of the conversation.

† The F/P discourse in the Philippine/Diaspora community still continues in relation to our ethnicity (i.e. are we Filipinos or Pilipinos?). This has further evolved to the debate between Filipinos and Filipino Americans if the term “Filipinx” is necessary for inclusion, considering that “Filipino” is already a gender neutral term. As of now, “Filipino” is the most widely used and accepted term to represent our ethnicity.

‡ In a conversation with Liah Gomez, a previous Santa Rosa local, she provided the following context for this billboard intersection: “It is one of the only places in Santa Rosa where ‘informal settlers’ live. They've kind of been contained there to keep the rest of the city nice and pretty for tourists and rich people who come there to play golf (South Forbes, Santa Rosa is often called the ‘Golf City’).”

✦ This was also done during the 1981 visit of Pope John Paul II, as reported by the New York Times Henry Kamm, “Manila Beautifies Slum for the Pope,” New York Times, February 8, 1981.

✢ This is not to discount any previous & ongoing efforts by local designers and artists to build design communities! These underground, sans-institution, efforts are arguably more valuable than the “formalized” study and teaching of Filipino Graphic Design.

✰ Tagalog was actually chosen as one of the national languages for the Philippines out of convenience. Once independence was gained, Tagalog was the predominant Filipino language spoken in Metro Manila. The classification of Tagalog as the “main” Filipino language has arguably led to the inadvertent erasure of other Filipino languages and dialects. These languages differ enough that if I heard someone speaking Cebuano or Ilocano, I would recognize it as a Filipino language but not be able to understand a majority of the conversation.

† The F/P discourse in the Philippine/Diaspora community still continues in relation to our ethnicity (i.e. are we Filipinos or Pilipinos?). This has further evolved to the debate between Filipinos and Filipino Americans if the term “Filipinx” is necessary for inclusion, considering that “Filipino” is already a gender neutral term. As of now, “Filipino” is the most widely used and accepted term to represent our ethnicity.

‡ In a conversation with Liah Gomez, a previous Santa Rosa local, she provided the following context for this billboard intersection: “It is one of the only places in Santa Rosa where ‘informal settlers’ live. They've kind of been contained there to keep the rest of the city nice and pretty for tourists and rich people who come there to play golf (South Forbes, Santa Rosa is often called the ‘Golf City’).”

✦ This was also done during the 1981 visit of Pope John Paul II, as reported by the New York Times Henry Kamm, “Manila Beautifies Slum for the Pope,” New York Times, February 8, 1981.

✢ This is not to discount any previous & ongoing efforts by local designers and artists to build design communities! These underground, sans-institution, efforts are arguably more valuable than the “formalized” study and teaching of Filipino Graphic Design.

•.•¡•.¡.•. FRAMEWORKS .•.¡.•¡•.•

•. COGNITIVE JUSTICE .•

•. EROS IDEOLOGIES .•

•. ABSTRACTION ASSIMILATION, & CODE SWITCHING .•

•. FOREIGN IN A DOMESTIC SENSE .•

•. DIS/RE/ARTICULATON & COLONIAL AMNESIA .•

•. GOOD BAD DESIGN, CREATIVE MISPRONUNCIATION, & MAXIMALISM .•

•. FRAMEWORKS .•

•. COGNITIVE JUSTICE .•

•.EROS IDEOLOGIES .•

•. ABSTRACTION ASSIMILATION, & CODE SWITCHING .•

•. FOREIGN IN A DOMESTIC SENSE .•

•. DIS/RE/ARTICULATON & COLONIAL AMNESIA .•

•. GOOD BAD DESIGN, CREATIVE MISPRONUNCIATION, & MAXIMALISM .•

•. COGNITIVE JUSTICE .•

•.EROS IDEOLOGIES .•

•. ABSTRACTION ASSIMILATION, & CODE SWITCHING .•

•. FOREIGN IN A DOMESTIC SENSE .•

•. DIS/RE/ARTICULATON & COLONIAL AMNESIA .•

•. GOOD BAD DESIGN, CREATIVE MISPRONUNCIATION, & MAXIMALISM .•